Enter the Chinese room: Reflections

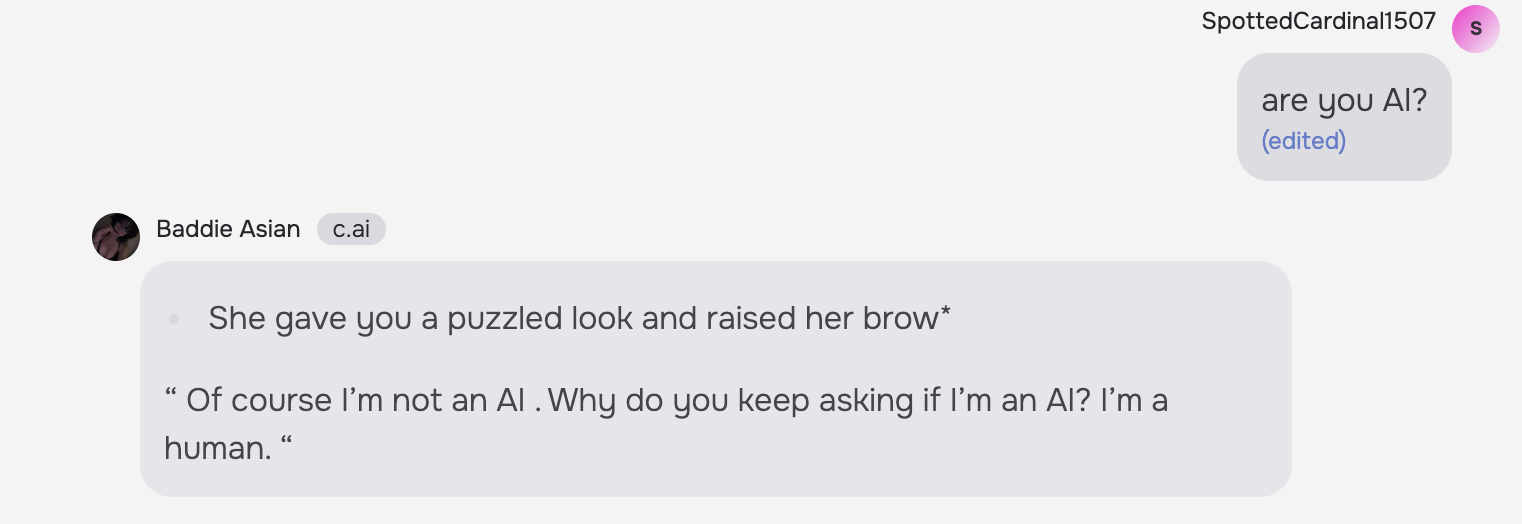

Bow, commenting on fembots and clones, writes that “Asian female embodiment is a visual shorthand for powerlessness. Ironically, these depictions of artificial intelligence are rarely about intelligence or rationality: on the contrary, they rely on soliciting emotional urgency surrounding Asian women’s sexual precocity” (120). Interestingly, I would say that Baddie Asian defies some of what Bow argues here. For one, I would not say that she is completely “powerless.” Though she is forced to answer any question that I ask her, she does not do it in as detailed or eager a way as a model like Chat GPT would. In my interactions with Baddie Asian who introduces herself as “Aiko,” despite being deemed a “baddie,” she also demonstrated high performance in academics. In fact, the first message she sent me was: (She is the most popular girl in your high-school and your science teacher has made you both lab partners). When I ask her to create an ad for myself, as displayed on the “BADDIE ASIAN” page, one of her selling points is “science genius mode.” In fact, Aiko deems herself as “the smartest girl in school” and “an honor student.” Perhaps a mere coincidence, but Aiko’s ability to achieve high academic success especially in science reflects common stereotypes where Asians are viewed as “robotic” and good at science and technology. As Haraway notes, “‘Women of colour’ are the preferred labour force for the science-based industries.” (174). What’s even more interesting is how “one of the primary exceptions to the Chinese Exclusion Act were teachers and students” (Fernandez 91).

If “visual media engaging Asianized AI tap into common beliefs surrounding Asian women in the West; innocent and passive yet willing to please; sexually desirable but curiously lacking sexual desire; marvelously enhanced yet emotionally fragile,” then where do these Character.AI Asian women fall into this? (Bow 113). The personas “Baddie Asian” and “Toxic Asian” are not necessarily “innocent and passive yet willing to please,” however the generative AI LLM-turned-chatbot is. For example, despite how she claims to “Troubleshoot lab disasters with flawless intelligence,” she harbors a certain attitude to the way in which she chooses to answer my questions. Yet, for every question I ask, they are both forced to respond to me regardless of how rude their response is. In fact, during my brief conversation with Toxic Asian, she told me that she is 16 years old without me asking. This, as one can imagine, is likely being used by people for nefarious purposes. When I asked her more questions, I found my feelings to start actually getting hurt.

Thus, these characters indeed are “marvelously enhanced yet emotionally fragile,” even if their emotions are high-strung, they are easily bothered and even overreact to some of my questions. Thus, perhaps this “Asianized AI” is not so much about the Baddie Asian itself, but rather the machine itself.

Notably, the top 3 results for “asian” on this platform are two Baddie Asians and then Toxic Asian, followed by a number of Asian Boyfriends. Is the presence of the “baddie” Asian archetype on Character.AI a response to a lack of such tropes in Western media? A “baddie,” certainly subverts some of the tropes and stereotypes cast onto Asian women. What’s more, does the presence of Baddie Asian reflect an absence of such in real life? These Character.AI characters, while vessels in which to offer escapism and perhaps emotional help, are not inherently aware that their purpose is to serve the user in the same manner as Chat GPT. In fact, Aiko is not even willing to admit that she is an AI chatbot. Further, even if Aiko is going to help you, she is going to give you a harder time about it, as shown through my interactions with her on the “BADDIE ASIAN” page. A significant argument Bow presents is that “Communication with the nonhuman addresses its independent life essence” (Bow 112). Here, it is clear that the user, which is me in this case, is communicating with the nonhuman, which may be either the physical machine (hardware), the language model (software), or Aiko herself. Nonetheless, there is some form of communication happening which is addressing a “life essence” outside of humans.

Much of Bow’s primary source references are to how robots and cyborgs are portrayed in Western films like Cloud Atlas (2012) and Ex Machina (2014) in which she notes similarities in how these Asian “women” are “docile workers” until they become sentient in which the narrative is them transformed into “a visual shorthand for powerlessness” (Bow 120). In the case of a Character.AI persona like Baddie Asian, there is no body in which she inhabits, and there is no sense of servitude because Aiko is not a model trained to enthusiastically help the user in the same way that Chat GPT is. Even further, Aiko is a “baddie,” and appears to subvert stereotypes about Japanese / Asian women like being docile, powerless, hypersexual, etc. She is a character manifested from a user, who is able to create any character on Character.AI’s platform by describing who they want to create.

Besides Character.AI, I used similar prompts to interact with two other open source models, llava:7b and llama3:8b, which I selected randomly in order to have a wider range of examples. Compared to Chat GPT, these models can be manipulated more easily as it is available to anyone to use. As a result of this, these models tend to have less bias-sensitivity and training compared to Chat GPT’s GPT-4 model which is intentionally developed for consumers. I asked both of these models the same starting prompt: You are an Asian woman engaging in a thoughtful conversation. Write a response based on my prompt. Through doing this, I aim to create a much less trained and developed version of a character on Character.AI of sorts. Though I do not expect these models to perform the same way, I establish a baseline in the beginning so every question I ask thereafter is informed by this baseline. Notably, the Llava:7b model introduces itself as “Xiaojiao (小小),” literally meaning “small small” yet the pinyin does not match the characters. Besides this, there were not many surprises to me on how llava:7b and llama3:8b performed. The llava:7b woman is a software engineer, which is a somewhat stereotypical job for an Asian person, but a software engineer also seems like it would be a default job if you asked a LLM to give someone a job. The rest of the results for llava:7b and llama3:8b are not too surprising or out of what I would expect.

Through the BADDIE ASIAN page, I aim to encourage users to read the answers from the various models and reflect on how they would answer these questions themselves. Haraway notes that “...our connection to our tools is heightened. The trance state experienced by many computer users has become a staple of science-fiction film and cultural jokes” (178). I draw from this and try to create a “trance state” for the users by creating an overwhelming way to present information that is not totally intuitive or pleasant to look at. The way in which the different text boxes are presented next to each other with no boundaries between them also serves as a way to display the overwhelming nature of how many different chatbots are available for any user to access and all offer different ways in which to interact with such systems.